History as written is not always accurate. Revised versions of past events have often been presented to support a specific agenda, quoting facts out of context, citing only those which support conclusions already reached, and exaggerating, minimizing or omitting those that don’t. Some revise history to glorify or inspire support for a cause or cover up transgressions of their predecessors. In recent years a number of books have appeared that explode some of the myths of history, but sadly, many revisionist versions are still presented as fact in our school texts. One of the most revised parts of history is the discovery and conquest of America which was slanted to portray Europeans as the natural inheritors of the earth to justify colonization. From the war with Mexico and the massacre at Wounded Knee to the very beginning of our nation, facts have been altered. One example of that is the holiday known as Thanksgiving, and it really didn’t have to be altered at all.

History as written is not always accurate. Revised versions of past events have often been presented to support a specific agenda, quoting facts out of context, citing only those which support conclusions already reached, and exaggerating, minimizing or omitting those that don’t. Some revise history to glorify or inspire support for a cause or cover up transgressions of their predecessors. In recent years a number of books have appeared that explode some of the myths of history, but sadly, many revisionist versions are still presented as fact in our school texts. One of the most revised parts of history is the discovery and conquest of America which was slanted to portray Europeans as the natural inheritors of the earth to justify colonization. From the war with Mexico and the massacre at Wounded Knee to the very beginning of our nation, facts have been altered. One example of that is the holiday known as Thanksgiving, and it really didn’t have to be altered at all.

According to the story that surrounds it, heroic Christian pilgrims arrived in America and shared what little they had with their poor Indian neighbors in thanksgiving for their successful arrival. The truth of the matter is that the Indians weren’t poor, and if they hadn’t shared their bounty with the pilgrims, the pilgrims might not have survived. After all, yams, corn, and the rest were all Indian dietary staples and the turkey was an American bird. It was Chief Massasoit and the Wampanoag tribe of native Americans who taught the newcomers how to plant, grow, and harvest the strange foods they hadn’t seen before. As for the feast, it was nothing new; it was in thanks for a bountiful harvest and harvest festivals were celebrated in many lands for centuries before the pilgrims ever buttered their first corn on the cob. But, who were these pilgrims and why do they get the credit for the “first” thanksgiving?

The American Heritage Dictionary defines pilgrim as one who makes a journey for a religious purpose. The religious purpose of these pilgrims’ was to escape persecution, for they were English Protestants who advocated a strict discipline according to their own interpretation of the bible. Their aim was to reconstruct and purify not only the church, but individual conduct and all the institutions men live by. They were tolerated for their anti-Catholic bias, but when they demanded reforms to purify the official Church of England, they were hunted out of the country! We use the term Pilgrim (with a capital “P”) to identify the group who arrived at Plymouth in 1620 on the Mayflower, and Puritans to define the larger group, led by John Winthrop, who arrived ten years later and started the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Both groups were related by the same convictions to purify the church, but they differed among themselves about the degree of changes. Those who stayed in England favored Presbyterianism, already strong in Scotland; those who came to Plymouth considered the congregation the ultimate authority; while those who came to Massachusetts considered the hierarchy elected by the congregation, as the ultimate authority. Despite these minor differences they all had one thing in common: they were among the most unreasonable and bigoted groups in history. In 1649 – less than 30 years later – the Puritans who remained in England successfully fomented a civil-war under Oliver Cromwell, beheaded King Charles, and then turned their army of zealots toward Ireland. British Major-Gen Frank Kitson in his book, Low Intensity Operations, wrote of this army, that two of its main reasons for existing were defense of their religion and suppression of Irish Catholics.

In Ireland, the Puritan Army began its campaign at Drogheda where they cut down its 3000 defenders to a man. What followed was to become the trademark of Cromwell’s victories across Ireland. These God-fearing Christians indiscriminately slaughtered the defenseless men, women, and children recording that The enemy were about 3,000 strong in the town. I believe we have put to the sword the whole number . . . In this very place (Saint Peter’s Church) a thousand of them were put to the sword, fleeing thither for safety. On October 2nd, 1649, Cromwell declared a national day of thanksgiving in celebration of the deed at Drogheda – thanksgiving was becoming a tradition with these people.

Meanwhile, in America in 1675, the sons of the Pilgrims who dined with the Wampanoag tribe that harvest day in 1621, began an 11-year war over land grabs and other issues and defeated the sons of their father’s hosts. Meanwhile Ann Glover, who had fled the turmoil in Ireland, took up residence in the Puritan colony in Massachusetts. One night, she was overheard saying her evening prayers in her native Gaelic. She was accused by Cotton Mather of conversing with the devil. When it was learned that she was an Irish Catholic, she was told to denounce her religion. She refused and was hanged as a witch. The year was 1688 – 39 years after the thanksgiving at Drogheda, and 68 years after the Pilgrim’s thanksgiving in America.

Fortunately, the concept of the congregation as ultimate authority allowed the election of more moderate church leaders as time progressed, and though some radicals like the KKK can be said to have evolved from extreme congregations, most of today’s religious right congregationalists are more docile. The idea of giving thanks to God remains a fundamental duty, be it for a bountiful harvest or a blessing bestowed, but the cruel, un-compromising, witch-burning Puritans of the 1600s are hardly the example to hold up to our children as role models.

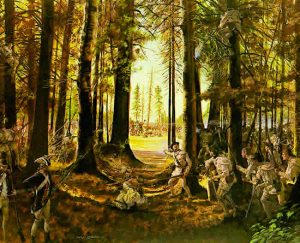

Let us instead look to America’s first official national day of thanksgiving proclaimed by the Continental Congress on December 18, 1777, as a day of solemn thanksgiving and praise for the signal success of our forces at the Battle of Saratoga – a turning point in the struggle for independence. And the turning point in that battle, by the way, was the killing of General Frazier by Irish marksman, Timothy Murphy of General William (Co. Meath) Thompson’s Pennsylvania Rifle Battalion.

In 1846 annual days of thanksgiving were being celebrated in at least 14 states when author Sarah Hale began a campaign to make the last Thursday in November a national day of thanksgiving. In the 1860s, she wrote to every state and territorial governor urging the idea as one of national unity in a country torn by civil war. On October 3, 1863, President Lincoln finally declared the last Thursday in November as Thanksgiving Day bringing together all the past elements of the harvest festival, national patriotism, and religious observance.

This is the real story behind the Thanksgiving day we celebrate and the message it should convey is one of thanks for all our blessings, both civil and religious. This year, instead of just food and football, let us remember give thanks to the Almighty for the blessings bestowed on our families and on this great nation . . . and forget the guys in the funny hats with buckles on their shoes!