In 1858, the Fenian brotherhood was founded in America and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in Ireland to work for Irish independence. Britain declared membership in that organization a crime punishable by deportation to her penal colony in Freemantle, Australia. Seldom in history can one find a story to rival the adventure that brought embarrassment to England and freedom to six Fenians who had been sentenced to that harsh penal colony for life.

In 1858, the Fenian brotherhood was founded in America and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in Ireland to work for Irish independence. Britain declared membership in that organization a crime punishable by deportation to her penal colony in Freemantle, Australia. Seldom in history can one find a story to rival the adventure that brought embarrassment to England and freedom to six Fenians who had been sentenced to that harsh penal colony for life.

It all began in 1871, when John Devoy, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, and other Fenians were released from prison in England on a general amnesty forced by public pressure after the Devon Commission authenticated the prisoner’s claims of cruelty and torture. Under terms of the amnesty however, the released Fenians were banished from Ireland; so they headed for America. In New York they joined Clan na Gael, a branch of the Fenian movement. At the same time, IRB man Thomas McCarthy Fennell arrived in New York in exile after a term at Freemantle, with terrible stories of those Fenians still imprisoned there. Fennell suggested a plan to liberate the prisoners still incarcerated there when, in 1873, Devoy received a letter from James Wilson, an IRB man still in Freemantle urging his liberation. Fennell and Devoy brought Fennell’s plan to John Boyle O’Reilly, who had escaped Freemantle in 1869. He advised stealth rather than force, and the three presented their plan to the Clan in 1873. At a Baltimore convention the following year, the plan was accepted and fund-raising initiated. As funds trickled in, Devoy and O’Reilly secured a sailing vessel named Catalpa at New Bedford, Mass. and outfitted her as a cargo ship bound for western Australia. On April 27, 1875, the ship set sail with only one Fenian on board. The rest of the rescue party sailed from San Francisco in September and arrived in Freemantle in November. Posing as officials on a tour of inspection, the Fenian leaders were given VIP treatment and taken on a tour of the prison facility by the Superintendent. It was on this tour that they made contact with the Fenian prisoners and arranged the escape.

Catalpa arrived early in 1876 but the scheduled rescue had to be postponed because of the arrival of new prisoners aboard a British gunboat. Catalpa was put in for minor repairs, in order to justify her delay in port, and the rescue was rescheduled for Easter Monday morning, April 17, 1876. On that morning, two rescue parties, each with horse and cart, left the city in different directions but bound for a prearranged rendezvous. The prisoners put their part of the plan in motion: prisoner Robert Granston approached a guard with a note from the Superintendent requesting prisoners James Wilson and Michael Harrington for a work detail at the Governor’s House. They were released and headed for the rendezvous. Prisoners Thomas Hassett and Thomas Darragh headed in the same direction as if going to work. They were joined by prisoner Martin Hogan who made an excuse for a brief absence to the guard of his work detail.

The good behavior of these men had given them a trustee status and this fact, coupled with the fact that escape from this isolated prison was considered all but impossible, accounted for the lack of security. Not long after the prisoners had fled the confines of the prison, their escape was discovered and the race was on to flee the pursuing authorities. At 10:30 AM, the prisoners met the rescue party, got into a waiting whale boat and rowed out toward Catalpa which had not been allowed to sail near the prison. When only two miles off shore, they spotted mounted police ride up to the spot where they had disembarked and take the horses and carts used by the rescue party. The Fenians continued rowing at a back-breaking pace for seven hours until heavy seas blew up about 5:30 PM – they were still almost 15 miles from Catalpa. They rode out the storm until morning when they spotted the British ship, Georgette, steaming out of Freemantle toward Catalpa. The authorities on Georgette did not spot the prisoners as they lay silently in the water but they ordered Catalpa on her way. As Georgette steamed back to Freemantle, the prisoners leaped to action and struggled off in the wake of Catalpa. Fearing that Catalpa was unaware of their presence the prisoners decided to risk discovery and wave to signal Catalpa before she sailed away. The gamble worked for Catalpa suddenly altered her course and headed for the whaleboat, but a police cutter also spotted the prisoners and steamed toward them as well. The game was up and it was only a question of who would reach them first. Catalpa won the race and the prisoners and their rescue party scrambled aboard. The police cutter signaled Georgette which returned flying a man-of-war flag. The Captain of Catalpa, knowing his ship was no match for the speed and armament of the British vessel, raised the American flag and waited. After a night of accusation and denial, threat and counterthreat, Georgette fired across the bow of Catalpa at 8:30 AM on the morning of April 19. The Captain of Catalpa shouted to Georgette, “If you fire on this ship, you fire on the American flag,” and ordered his crew to ready themselves for a fight to the finish. The Captain of Georgette, fearing an international incident, lingered awhile and slowly steamed away.

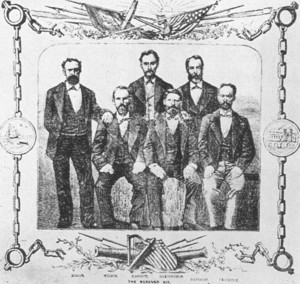

When word reached O’Reilly, he released the news to the press. It was received with celebrations in America and Ireland and anger in England. A purge of prison officials in Freemantle followed as, in August, 1876, six patriotic Irishmen sailed into New York Harbor in the good ship Catalpa as a result of Irish daring and Yankee grit.