The rebirth of the Olympic games occurred in 1896 and the first of the modern games was held in Athens, Greece. Bill Mullins 1998 book on the 1896 Olympics records that James Connolly became the first known Olympic champion since Zopyros of Athens in the 291st games held in 385 AD. Connolly was born in Boston of Aran Island immigrant parents. He was only one of a group of Irish-born Olympic athletes who competed for the United States. A group nicknamed the Irish Whales dominated track and field events, particularly throwing events, for the United States, for the first two decades of the 20th century. Between 1896 and 1924, the whales won everything from the Amateur Athletic Union national championships right up to the Olympic Games. They were primarily members of the Irish American Athletic Club, the New York Athletic Club and, with the exception of Connolly and Simon Gilles, they were also members of the New York City Police Department. They were known as the Whales because of their athletic ability, huge size and voracious appetites.

The rebirth of the Olympic games occurred in 1896 and the first of the modern games was held in Athens, Greece. Bill Mullins 1998 book on the 1896 Olympics records that James Connolly became the first known Olympic champion since Zopyros of Athens in the 291st games held in 385 AD. Connolly was born in Boston of Aran Island immigrant parents. He was only one of a group of Irish-born Olympic athletes who competed for the United States. A group nicknamed the Irish Whales dominated track and field events, particularly throwing events, for the United States, for the first two decades of the 20th century. Between 1896 and 1924, the whales won everything from the Amateur Athletic Union national championships right up to the Olympic Games. They were primarily members of the Irish American Athletic Club, the New York Athletic Club and, with the exception of Connolly and Simon Gilles, they were also members of the New York City Police Department. They were known as the Whales because of their athletic ability, huge size and voracious appetites.

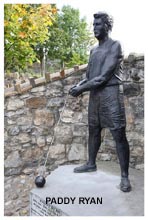

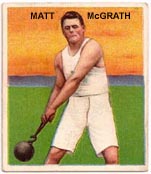

The Irish Whales were John Jesus Flanagan of Co. Limerick, James Sarsfield Mitchell of Tipperary, Pat McDonald of Clare (affectionately known as the Times Square Traffic Cop), Paddy Ryan of Limerick, Martin Sheridan of Mayo, Matt McGrath of Tipperary and Simon Gilles from Nova Scotia. Sheridan at 6’3″ and 194 pounds was the lightest of the group but what he lacked  in girth, he made up for with his appetite and athletic accomplishments, winning nine Olympic medals in all. Matt McGrath was built like a wedge. He was a six-footer, but he weighed 248 pounds. John Flanagan was about the same. Simon Gilles was 6’2″ and 240. Paddy Ryan was 6’5″ and 296, and Pat McDonald was 6’5″ and 300 pounds.

in girth, he made up for with his appetite and athletic accomplishments, winning nine Olympic medals in all. Matt McGrath was built like a wedge. He was a six-footer, but he weighed 248 pounds. John Flanagan was about the same. Simon Gilles was 6’2″ and 240. Paddy Ryan was 6’5″ and 296, and Pat McDonald was 6’5″ and 300 pounds.

Arthur Daly in the New York Times, wrote of how they got their nicknames on the train trip to the Olympics of 1912. He wrote. Those big fellows all sat at the same table and their waiter was a small chap. Before we reached Stockholm he had lost twenty pounds, worn down by bringing them food. Once as he passed me he muttered under his breath, ‘It’s whales they are, not men.’ They used to take five plates of soup as a starter and then gulp down three or four steaks with trimmings. That Simon Gillis would think nothing of having a dozen eggs for breakfast. And, they were also the life of any party.

Another tale of their voracious appetites came from Daly twenty-two years later. In a Times column he wrote: Some of their more prodigious feats were at the table. The Irish American A.C. was competing in Baltimore when Gilles placed an order for a post-meet snack with the head waiter at a local restaurant. He ordered 27 dozen oysters and six huge T-bone steaks. The waiter was ready when Gilles, McDonald and McGrath arrived. The table had been set for a party of 6. ‘Do you want to wait for the rest of your group?’ asked the headwaiter. He turned pale as he watched three whales devour 27 oysters and six huge T-bone steaks.

On a tragic note, in 1904, Gilles accidentally killed a boy when he was practicing his hammer throw in a vacant lot on Park Ave and 134th Street. Just as he had let the 16 pound hammer go for an extra long throw, a fourteen-year old boy, climbed the fence in pursuit of a baseball. Gilles and several boys shouted a warning, but the boy didn’t hear. The hammer struck him in the head and he was instantly killed. Gilles was heartbroken over the affair.

In 1905, while attached to the 37th Precinct, Flanagan competed in the Police Athletic Association games held at Celtic Park in Sunnyside, New York. Not only did he win four of weight-throwing events, but entered the fat men’s race, and won that, giving him a total of five first place victories. In the 1908  Olympics in London, Flanagan broke his own record with a hammer throw of 170 feet, 4.5 inches. The silver that year went to another New York City police officer, the former record holder Matt McGrath. On July 24, 1909, Flanagan became the oldest world record breaker at age 41, when he threw the hammer 184 feet, 4 inches. When his father died in 1924, Flanagan returned to Ireland where he died in 1938.

Olympics in London, Flanagan broke his own record with a hammer throw of 170 feet, 4.5 inches. The silver that year went to another New York City police officer, the former record holder Matt McGrath. On July 24, 1909, Flanagan became the oldest world record breaker at age 41, when he threw the hammer 184 feet, 4 inches. When his father died in 1924, Flanagan returned to Ireland where he died in 1938.

Sheridan meanwhile won six Olympic medals in throws and three in jumps for the U.S. making him the most successful Irish olympian of all times and in 1924, at age 45, McGrath became the oldest American track and field medal winner in a throwing event with his silver medal – a record that still stands.

Perhaps the most memorable legacy of these great athletes was set at the 1908 Summer Olympics which were held in London where many medals were won by Irish athletes representing America, not the least of which were the Irish Whales. During the Parade of Nations, it was a customary for teams to dip their nation’s flags as a show of respect for the ruling monarch of the host country. Patrolman Martin J. Sheridan was part of the American Olympic team parading. Everyone knew Sheridan held a grudge against the  English because of their inaction during the Great Hunger 60 years earlier. Coaches of the Olympic committee, knowing his dislike for the English, replaced Sheridan, who was scheduled to carry the American flag, with Ralph Rose as flag bearer. It should be noted that the Irish in America also had a strong sense of patriotic pride to their new-found country and as the American team approached the Royal Box, team member Matt McGrath broke ranks and stepped up to the American flag bearer and said, Dip that flag and you will be in a hospital tonight. The flag was not dipped. It caused an international incident. During a news conference later, Martin Sheridan spoke for the entire Olympic team when he pointed to the American flag and said, That flag dips to no earthly king. A precedent was set, and that precedent is still followed to this day. During the Olympic Games or on any occasion on land or at sea, the American Flag has never been dipped to anyone since that day in 1908. In fact, the United States Flag Code was officially changed to read, No disrespect should be shown to the flag of the United States of America; the flag should not be dipped to any person or thing.” (Title 4, U.S. Code, Chapter1 § 8). Watch for history to be repeated this month as the Olympic games return to London.

English because of their inaction during the Great Hunger 60 years earlier. Coaches of the Olympic committee, knowing his dislike for the English, replaced Sheridan, who was scheduled to carry the American flag, with Ralph Rose as flag bearer. It should be noted that the Irish in America also had a strong sense of patriotic pride to their new-found country and as the American team approached the Royal Box, team member Matt McGrath broke ranks and stepped up to the American flag bearer and said, Dip that flag and you will be in a hospital tonight. The flag was not dipped. It caused an international incident. During a news conference later, Martin Sheridan spoke for the entire Olympic team when he pointed to the American flag and said, That flag dips to no earthly king. A precedent was set, and that precedent is still followed to this day. During the Olympic Games or on any occasion on land or at sea, the American Flag has never been dipped to anyone since that day in 1908. In fact, the United States Flag Code was officially changed to read, No disrespect should be shown to the flag of the United States of America; the flag should not be dipped to any person or thing.” (Title 4, U.S. Code, Chapter1 § 8). Watch for history to be repeated this month as the Olympic games return to London.

During his police career McGrath attained the rank of Inspector, and was awarded the NYPD’s Medal of Valor twice. Inspector McGrath died in January of 1941. Martin Sheridan helped organize the Police Carnival and Games, for the benefit of the welfare fund of the Department, and which, for many years, was an outstanding athletic event in New York. To perpetuate his name for future generations the Martin J. Sheridan Award for Valor was established, and given each year to a member of the Police Department for bravery above and beyond the call of duty. Sheridan, a First Grade Detective died of pneumonia in on March 25, 1918 while working a double shift for a sick NYPD colleague. He was just thirty-seven and is buried in Calvary Cemetery, Woodside, New York.

During his police career McGrath attained the rank of Inspector, and was awarded the NYPD’s Medal of Valor twice. Inspector McGrath died in January of 1941. Martin Sheridan helped organize the Police Carnival and Games, for the benefit of the welfare fund of the Department, and which, for many years, was an outstanding athletic event in New York. To perpetuate his name for future generations the Martin J. Sheridan Award for Valor was established, and given each year to a member of the Police Department for bravery above and beyond the call of duty. Sheridan, a First Grade Detective died of pneumonia in on March 25, 1918 while working a double shift for a sick NYPD colleague. He was just thirty-seven and is buried in Calvary Cemetery, Woodside, New York.

America’s Irish continued to dominate Olympic throwing events for the U.S. team until the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics when the U.S. lost for the first time in the hammer throw event – they lost to an Irishman, Dr. Patrick O’Callaghan who was competing for the new Irish Free State. He had been trained by John Flanagan!