Wallabout Bay is small body of water along the northwest shore of Brooklyn, NY. In 1801, a settlement called Vinegar Hill was built on that bay to attract Irish immigrants to settle there and provide the labor to build the Brooklyn Navy Yard which opened in 1806. However, Vinegar Hill was built on an area which, 20 years earlier, had seen incredible horror!

During the American Revolution, the British had captured thousands of soldiers, sailors, and even private citizens who would not swear allegiance to the Crown. When they ran out of jail space to house their prisoners they used ship hulls, no longer seaworthy, anchored in Wallabout Bay as floating prisons. Conditions were so terrible that more Americans died on these prison ships than in all the battles of the Revolution! According to the U.S. Dept of Defense, there were 4,435 battle deaths during the War yet more than 11,500 died from neglect, cruelty and disease on these rotting hulls. William Burke, a prisoner aboard the prison ship Jersey, wrote, At night, when the prisoners were assembled at the hatchway, for the purpose of obtaining fresh air, one of the sentinels would thrust his bayonet down among them, and one morning twenty-five of them were found wounded, and stuck in the head, and dead of the wounds they had thus received. I further recollect that this was the case several mornings, when sometimes eight or ten, were found dead by the same means. The dead would be carried ashore and buried in the sand in shallow graves, or simply thrown overboard.

Among the patriots imprisoned were a great many Irish. In 1888, the Society of Old Brooklynites published a pamphlet which gave the names of those confined on the ship Jersey. From that source, John D Crimmins in Irish American Miscellany (1905) lists at least 363 Irish names and reports that many more could be added, but these were sufficient to make his point that a large number of the sons of Erin were among those who suffered on the prison ships. Capt. Thomas Dring, who was imprisoned aboard the Jersey, added, There were continual noises during the night. The groans of the sick and dying; the curses poured out by the exhausted upon our inhuman keepers; the restlessness caused by the suffocating heat and the confined and poisonous air, mingled with the wild and incoherent ravings of delirium, were the sounds which, every night, were raised around us in all directions. Another writer stated, Dysentery, smallpox, and yellow fever broke out, and while so many were sick with raging fever, there was a loud cry for water; but none could be had, except on the upper deck. One incident is recorded regarding a prisoner, who died on the Jersey: Two young men, brothers, were prisoners on board the ship. The elder took the fever, and, in a few days became delirious. One night (his end was fast approaching) he became calm and sensible, and lamenting his hard fate, and the absence of his mother, begged for a little water. His brother, with tears, entreated the guard to give him some, but in vain. The sick youth was soon in his last struggles, when his brother offered the guard a guinea for an inch of candle, only that he might see his brother die. Even this was denied. ‘ Now,’ said he, drying up his tears, ‘ if it please God that I ever regain my liberty, I’ll be a most bitter enemy!’ He regained his liberty, rejoined the army, and when the war ended, he had eight large, and one hundred and twenty-seven small notches on his rifle stock. After the surrender at Yorktown in 1781, the fighting ended, but the cruelty on the prison ships continued until the Treaty of Paris was signed and the Brits left New York, two whole years later, in 1783!

In the History of the City of Brooklyn, author Henry Stiles narrates a scene that took place on July 4, 1782, after the war was over, as prisoners attempted to celebrate the anniversary of Independence Day. He wrote: A very serious conflict with the guard occurred in consequence of the prisoners attempting to celebrate the day with such observances as their condition permitted. Upon going on deck in the morning, they displayed thirteen little national flags in a row upon the booms which were immediately torn down and trampled under the feet of the guard. Deigning no notice of this, the prisoners proceeded to amuse themselves with patriotic songs, speeches, and cheers, all the while avoiding whatever could be construed as an intentional insult of the guards who, at an unusually early hour in the afternoon, drove them below at the point of the bayonet, and closed the hatches. Between decks, the prisoners now continued their singing, until about nine o’clock in the evening. An order to desist not having been promptly complied with, the hatches were suddenly removed, and the guards descended among them with cutlasses in their hands. Then ensued a scene of terror. The helpless prisoners, retreating from the hatchways as far as crowded condition would permit, were followed by the guards, who mercilessly hacked, cut, and wounded everyone within their reach; and then ascending again to the upper deck, fastened down the hatches upon the poor victims of their cruel rage, leaving them to languish through the long, sultry, summer night, without water to cool their parched throats, and without lights by which they might have dressed their wounds. And to add to their torment, it was not until the middle of the next forenoon, that the prisoners were allowed to go on deck and slake their thirst, or to receive their rations of food, which, that day, they were obliged to eat uncooked. Ten corpses were found below on the morning following that memorable 4th of July and many others were badly wounded. And the war had been over for 10 months!

In a letter to Naval Magazine, General Jeremiah Johnson wrote, It was no uncommon thing to see five or six dead bodies brought on shore in a single morning, when a small excavation would be dug at the foot of the hill, the bodies be thrown in, and a man with a shovel would cover them. The whole shore was a place of graves; as were also the slope of the hill, the shore and the sandy island. The atmosphere seemed to be charged with foul air from the prison-ships, and with the effluvia of the dead bodies washed out of their graves by the tides. We believe that more than half of the dead buried on the outer side were washed out by the waves at high tide. The bones of the dead lay exposed along the beach, drying and bleaching in the sun, till reached by the power of a succeeding storm; as the agitated waters receded, the bones receded with them into the deep. For years after, the bones of these martyrs to American freedom were visible along the shore.

Stiles noted, There was however, one condition upon which these hapless sufferers might have escaped the torture of this slow but certain death, and that was enlistment in the British service. This chance was daily offered them by the recruiting officers who visited the ship, but their offers were almost invariably treated with contempt by men who fully expected to die. In spite of untold physical sufferings, which might well have shaken the resolution of the strongest; in spite of the insinuations of the British that they were neglected by their government; in defiance of threats of even harsher treatment, and regardless of promises of food and clothing, but few sought relief from their woes by the betrayal of their honor. And these few went forth into liberty followed by the undisguised contempt of the suffering heroes whom they left behind. It was this calm, unfaltering, unconquerable spirit of patriotism, defying torture, starvation, loathsome disease, and the prospect of a neglected and forgotten grave, which sanctifies to every American heart the scene of their suffering in the Wallabout, and which will render the sad story of the ‘prison-ships ‘ one of ever increasing interest to all future generations. As a footnote to the tragedy, the Brit Commander of the prison ships was charged with war crimes and subsequently hanged.

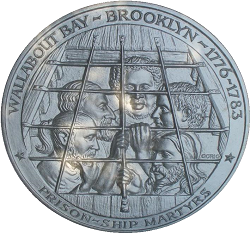

Eighteen years later, when the community of Vinegar Hill was established, residents were shocked by the skeletal remains of the prison ship victims exposed along the shoreline. During the summer of 1805, local Irish women began collecting the remains when they became exposed or washed ashore. The bones were saved and finally interred in a vault patriotically erected by the Tammany Society. The corner stone of the vault for the bones of the martyred dead, was laid in April, 1808 and marked with a great demonstration, a military and civic parade in the city and artillery salutes. When completed, the bones were re- interred in 13 thirteen coffins, with veterans of the Revolution acting as pall bearers. Stiles records that, The procession, after passing through various streets, reached the East River, where, at different places, boats had been provided for crossing to Brooklyn. Thirteen large open boats transported the thirteen tribes of the Tammany Society, each containing one tribe, one coffin, and the pall-bearers. The scene was most inspiring. At Brooklyn, the procession formed again and arrived at the tomb of the martyrs amidst a vast and mighty assemblage. There was an invocation by Rev. Ralph Williston. The coffins were huge in size and each bore the name of one of the thirteen original states. The first grand sachem of Tammany was William Mooney, a man of Irish extraction and leader of the Sons of Liberty – a patriot society formed before the Revolution. By the 1840s, the monument was in a state of disrepair. In 1873 a large stone crypt was constructed in the heart of what is now Fort Greene Park, and the bones were re-interred therein. A small monument was erected on the hill above the crypt. By the close of the 19th century, funds were raised for a more fitting memorial – a 148 ft. tower which stands today in Fort Greene Park (www.fortgreenepark.org) and was unveiled in 1908 by President Taft. Today, the Prison Ship Martyrs Memorial marks the site of a crypt containing the bones of more than 11,500 of America’s prison ship martyrs.