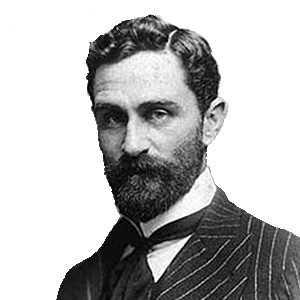

The last patriot to be executed for his part in the Easter Rising of 1916 was a Protestant from Northern Ireland further disproving the North vs South, Catholic vs protestnat mythology promoted by the British to divide and conquer. His name was Roger Casement and he was born in Antrim on September 1, 1864 to a Protestant father and Catholic mother. At 17, he went to work for the Elder Dempster Shipping Company in Liverpool; three years later he shipped out as purser on one of the company’s ships headed for the west coast of Africa. There in 1892 he joined the British Colonial Service and was gradually advanced to a position of trust in the British Consulate. Always a fair and honorable man, Casement was horrified at the inhuman treatment of native workers in the Belgian Congo, and wrote a notable report exposing those conditions. The story was published in the press, and when Casement returned to England in 1904. He was the man of the hour.

While in London he met Alice Stopford Green, a historian who argued that the English had no right in Ireland, and denounced the exploitation of the Irish people. She had a profound influence on Casement and when he returned to Ireland he looked up her friends: Bulmer Hobson, Eoin MacNeill, and Erskine Childers. He soon became a confident of these and other men of similar political convictions.

Casement’s diligent service earned him the post of Consul General at Rio de Janeiro and he sailed off to assume that enviable post, but even there his sense of fair play guided his actions. He wrote a scathing report on the cruelties practiced by whites on native workers on the rubber plantations along the Putamayo river. It became an international sensation. He returned to England in 1911 and was Knighted for his public service. Casement retired from the Colonial Service in 1912 and returned to Ireland where his sense of fair play was again aroused – this time by the conditions of his own people under the rule of the Crown.

Always a man of strong nationalist sympathies, he joined the National Volunteers in 1913. When he visited London during the following year, the knighted Sir Roger was on a different mission – to arrange for the Irish Volunteer Corps to bring 1500 Hamburg guns to Howth. History shows just how successful he was for many a man marched into Dublin on Easter Monday morning shouldering his old Howth gun. But lets not get ahead of our story. More money was needed to secure more arms, and Casement was entrusted with a trip to New York to see the gallant old Fenian, John Devoy who had been busy raising funds for that purpose among the American Irish. On July 4, 1914, Casement sailed for America. While he was in America, World War I broke out, and Devoy contacted the German ambassador to America seeking aid to win Irish independence. On October 15, 1914 Casement sailed from New York to Germany, carrying a small fortune in Clan na Gael money to purchase more arms. He also hoped to enlist Irish prisoners-of-war in a brigade to serve in an Irish rising, but in that he was not successful. However, the Germans did dispatch the ship AUD with a cargo of arms to be landed at Banna Strand in Co Kerry. Casement followed in a submarine, landing on Banna Strand in Tralee Bay on Good Friday, 1916. Those who were to meet him there did not.

American Federal agents had raided the New York office of the German Attache and confiscated many documents including Devoy’s message concerning the arms shipment. A delay of 24 hours and an alternate landing spot was radioed to the AUD, but the ship’s radio was inoperative. The Aud landed at the original landing spot and a British convoy was waiting for them. the Aud was escorted by the British to Cork and on the was the German Captain scuttled the ship! The bewildered Casement decided to wait on the beach until his contacts arrived, but he was captured, identified and hurried away to London as a prisoner. An angry Devoy blamed American President Wilson for alerting the British to the arms shipment even though it was a legal transaction since American had not yet entered the war, but because Wilson was of northern Irish loyalist heritage.

Found guilty of high treason, Casement was sentenced to be hanged. A world-wide furor erupted over the severity of the sentence. Here was a just man, recently praised and knighted by the Crown for his efforts on behalf of persecuted natives in far corners of the world, sentenced to death by that same Crown for daring to challenge the exploitation of his own downtrodden people. In an effort to reverse public opinion, the British government circulated copies of diaries alleged to be Casement’s, which recorded homosexual practices. Much controversy surrounded these Black Diaries, but they had the desired effect. The public furor died down, and Casement was hanged in Pentonville Prison on August 3, 1916.

For many years after the Irish government finally won its limited freedom from England, official requests were made to have Sir Roger’s remains returned to Ireland. It was not until 1965, that the English Government finally relented, but only after circulating the despicable Black Diaries once more. But this time they didn’t reckon on modern analytical methodology, and the diaries were claimed by many experts to be forgeries. In spite of English efforts to sully the name of this dedicated Irish patriot, Casement’s remains were respectfully received by the Irish people, given a huge state funeral, and re-interred in Glasnevin Cemetary on March 1, 1965 – just one year before the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising.