After the American Civil War, the Fenian brotherhood felt the time was right for a long-awaited national rising in Ireland. In February 1867, a small local rising in Cahirciveen, Co. Kerry, finally prompted a national rising which took place on 6 March. Thousands of Fenians took to the hills, but poorly armed, they were easily put down and hundreds were jailed. Unaware of the failure of the rising, support was sent from America’s Fenians. On 23 May, the ship Erin’s Hope with 40 Fenians (former Civil War officers), 5,000 firearms and several artillery pieces on board sailed into Sligo Bay. After unsuccessful attempts to contact Fenians on shore, they sailed to a port outside Waterford where most of the crew disembarked and were captured. More landings were attempted, but upon learning of the failure of the rising, those on board decided to return to America. The hope of freeing Ireland by militant means had once again been frustrated.

Meanwhile, two Fenians, Thomas Kelly and Timothy Deasy, escaped to England to reorganize Fenians there. Both had been American Civil War officers. Kelly had been declared Head of the Irish Republic and Deasy, a member of Lawrence, MA AOH Div. 8, led a Fenian brigade. On 11 September 1867, they were arrested in England and on the 18th were bound for Belle Vue Jail in a police van escorted by 12 mounted police. As the van passed under a railway arch, about 35 men leaped over a wall, surrounded the van and seized the horses. The unarmed police fled. The rescuers called on Sgt. Brett, inside the van, to open the locked door. Brett refused, so one of the rescuers placed his revolver at the keyhole of the van to blow the lock unaware that Brett just bent over to look through the keyhole and see what was happening outside. The bullet killed him instantly. The door was unlocked with keys taken from Brett’s pocket by another prisoner in the van. The van was opened and Kelly and Deasy were free.

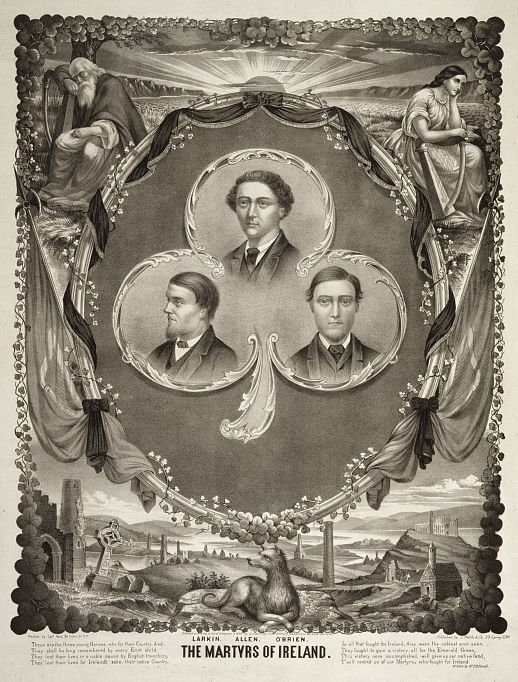

The rescue was the only bit of positive news after the failure of the rising. However, vengeful British police invaded the Irish section of Manchester and brought in dozens of suspects arbitrarily seized in raids that were described as a ‘reign of terror’. Of those apprehended, 26 were sent to trial. It was decided to charge five, selected at random, as the principal offenders: William Allen, Michael Larkin, Michael O’Brien, Edward Condon and Thomas Maguire. Despite the fact that none of them fired the fatal shot, the vengeful jury returned a verdict of guilty for all. When asked if they had anything to say, Allen stated his innocence and Larkin said ‘I forgive all who have sworn my life away.’ O’Brien claimed that all the evidence against him was false and, as an American citizen, he ought not to face trial in a British court. Condon admitted to having organized the attack in his role as a Fenian leader, but claimed that he never threw a stone or fired a pistol; I was never at the place, it is all totally false. At the end of his testimony he shouted, God save Ireland! The cry was taken up by his companions in the dock. Allen, Larkin, O’Brien, Maguire and Condon were all sentenced to death by hanging, once again crying ‘God save Ireland’ after each sentence was pronounced – a phrase that has been immortalized in song.

The trial took place in a climate of anti-Irish hysteria said the weekly Reynold’s Newspaper, which described it as a deep and everlasting disgrace to the English government. In Maguire’s case the witnesses who testified that Maguire was in the forefront of the attack had their evidence disproved. An appeal resulted and Maguire was granted a pardon. Many believed that the others would also be saved since they had been convicted on evidence by the same witnesses who perjured themselves against Maguire. Condon was pardoned on the eve of his execution, but Allen, Larkin and O’Brien were not as fortunate for scapegoats were required. Throughout Manchester, silent congregations attended Mass for the souls of the three innocent Irishmen doomed to die on 23 November. To make matters worse, the executioner was incompetent and miscalculated the correct length of rope required to break the neck of each victim. When the trap floor was released, Allen died almost instantly from a broken neck, but Larkin and O’Brien did not. A local priest in attendance, Father Gadd, reported that the other two ropes were stretched taut and tense by their still breathing, twisting burdens. The hangman had bungled the job! He then descended below the scaffold and there finished what he could not accomplish from above; to pull on his victim’s legs to hasten death – in that manner he killed Larkin. Father Gadd refused to allow the hangman to dispatch O’Brien the same way and for three-quarters of an hour the priest knelt, holding the dying man’s hands within his own, reciting the prayers for the dying. Then the long drawn out agony ended. He did O’Brien no favor!

The bodies were callously buried in quicklime graves in unconsecrated ground in the prison. When the prison closed in 1868, the remains were exhumed and re-buried in Strangeways Prison. In 1991 the remains were exhumed once again and re-interred in Blackley Cemetery, Manchester where reports of desecration of the grave have been reported. Former AOH National Historian Col. Robert Bateman, a descendant of the rescued Capt. Timothy Deasy and a member of the Peekskill AOH Div 18 is seeking support to have the remains exhumed once again and this time repatriated to the consecrated grounds of Glasnevin cemetery where Ireland’s heroes sleep. He is seeking supporters to assist a committee in accomplishing this deed in time for the 150th Anniversary of their unwarranted execution on November 23, 2017. If you can help or need more information contact brother Batemen at rjpbateman@gmail.com