On March 27, 1872, Mary MacSwiney (Maire Nic Shuibhne) was born in Surrey, England, of an Irish father and an English mother. She grew up in Cork beset by illness which culminated with the loss of an infected foot. Educated as a teacher, by 1900 she was teaching in a convent school. Her mother’s death in 1904 led to her return to Cork to head the household and secure a teaching post back at St Angela’s. The MacSwiney household was intensely separatist. They read Arthur Griffith newspaper, although they rejected his dual monarchy policy. She refused to join Griffith’s Sinn Féin because she said, I will never accept the King of England as King of Ireland. However, she would join in 1917 when it became more Republican.

On March 27, 1872, Mary MacSwiney (Maire Nic Shuibhne) was born in Surrey, England, of an Irish father and an English mother. She grew up in Cork beset by illness which culminated with the loss of an infected foot. Educated as a teacher, by 1900 she was teaching in a convent school. Her mother’s death in 1904 led to her return to Cork to head the household and secure a teaching post back at St Angela’s. The MacSwiney household was intensely separatist. They read Arthur Griffith newspaper, although they rejected his dual monarchy policy. She refused to join Griffith’s Sinn Féin because she said, I will never accept the King of England as King of Ireland. However, she would join in 1917 when it became more Republican.

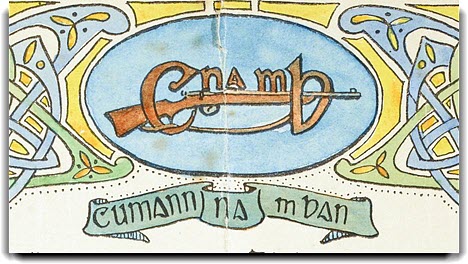

The first Republican speech Mary attended was at the Centenary Celebration in 1898 where she heard John Redmond give a fiery rebel speech. Seeking more information, she read a speech he made in England, a few days later, in which he assured England that the Ireland would never dream of taking control of excise, customs or taxation from England. She was appalled by the glaring contrast and, influenced by her revolutionary brother Terence MacSwiney, she joined the Gaelic League and Inghinidhe na hÉireann, a nationalist women’s organization that would form the basis of Cumann na mBan. Women’s suffrage was also a cause with which was associated. A founding member of the Munster Women’s Franchise League (MWFL) in 1911, she explained to a friend who criticized her actions that she sought votes for women as a matter of justice.

However, it was the third Home Rule crisis that brought a change to her focus. After her brother and Tomás MacCurtain founded a Cork branch of the Irish Volunteers in 1914, Mary founded a Cumann na mBan branch and left the MWFL. She acted as a courier and was in Cork city after Easter, 1916, to see the arrest of her brother and other Volunteer leaders. She led a campaign for their release in the aftermath of the 1916 executions that took her to Dublin Castle and to the House of Commons itself. Her return to teaching duties at St Angela’s after Easter week was shattered when the RIC arrested her in class, causing her dismissal. That led her to founding her own school in September 1916 with her sister Annie; they opened Scoil Íte on the model of Pearse’s St Enda’s – an Irish-Ireland school.

In 1917, her election to Cumann na mBan’s national executive marked her ascent to her first leadership role at national level. Now also an active member of Republican Sinn Fein, she campaigned for her brother Terence when he was elected to the first Dáil Éireann in 1918 and as Lord Mayor of Cork in 1920. She also supported his fatal hunger strike in Brixton Prison just two months later. Together with her sister, Annie, and Terence’s wife, Muriel, their vigil at Brixton prison was a key part of the hunger strike drama played out in front of the world’s press. But it was his death after a 74-day ordeal that propelled her to national prominence. After his death on 25 October 1920, she assumed a large part of her brother’s heroic mantle. In early 1921, she and Terence’s widow spent nine months in the US giving evidence before the American Commission on Conditions in Ireland, lecturing and giving interviews providing invaluable publicity to the Republican cause.

In the General Elections of 1921, as President of Cumann na mBan, Mary was one of the Sinn Féin candidates swept to victory in a wave of support for the party. Opposing the Anglo-Irish Treaty, her speeches were among the most powerful, calling on the Dáil not to take an oath of allegiance to the British Monarch. Her 2-hour, 40-minute speech in the Dáil on 21 December 1921 was the longest of the treaty debates. She was Vice President of Cumann na mBan when that organization voted 419 to 63 against supporting the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty. After the Treaty was ratified, Cumann na mBan, following a resolution by Mary, was the first national organization to reject the formation of the Free State. After the majority voted in favor of the treaty, she emerged with a reputation for being one of the leading Republicans, yet she was prepared, like Cathal Brugha and Austin Stack, in the interests of unity, to accept the compromise proposed by Éamon de Valera, bnt Britain refused to accept the compromise and civil war ensued. She was re-elected to the third Dáil which, owing to the outbreak of the Civil War, was never to sit.

In July 1922, she was imprisoned by the Free State authorities, went on a hunger strike, and was released. After the cease-fire, she retained her seat in the General Election of 1923 but, like other Republican deputies, refused to take the Oath of Allegiance. In June 1921 she was elected to the Dáil for Cork city. An uncompromising Irish republican, Mary fought the civil war in a non-combatant role, but was arrested twice. She went on hunger strike in November 1922 and April 1923 and was released each time as a result of public pressure. When deValera compromised in 1926 in order to enter the Dáil, MacSwiney held fast to her Republican ideals, still refusing to take the oath to the Crown. In 1933, she founded Mná Poblachta (Republican Women) in opposition to Cumann na mBan, which she believed was moving too far left.

Mary MacSwiney died at her home in Cork on March 8, 1942, just weeks before her 70th birthday. She had risen from the ranks of the suffragist movement and was one of the first generation of newly enfranchised women to become a leader in Irish politics. Her credentials as a progressive Irish-Ireland educationist in her own school was recognized by friend and foe alike, but her uncompromising stand for the ideals of the heroes of 1916 mark her as one of the foremost Republicans of her age.