In the mid 1800s, American Party (Know Nothings) were violently against Catholic immigrants and rioting took place in many Irish neighborhoods across the country. One of the most violent took place in Louisville, KY on 6 August 1855. It was election day and nativists were against allowing Catholics to vote. Irish and German immigrants, most of them Catholic, made up nearly a quarter of Louisville’s population of 43,000 at the time, but most native-born residents were Protestant and many were members of the American Party.

George Prentice, editor of the Louisville Daily Journal newspaper, a predecessor of The Courier-Journal, was widely accused of inflaming the mobs in editorials in the days before the riot. He denounced: the most pestilent influence of the foreign swarms, loyal to a pope he called: an inflated Italian despot who keeps people kissing his toes all day. The next day the paper reported: On Sunday night, large detachments of men were sent to the First and Second Wards to see that the polls were properly opened. These men, the “American Executive Committee” supplied with the requisite refreshments, and as may be imagined they were in very fit condition to see that the rights of freemen were respected. Indeed they discharged the important trusts committed to them in such manner as to commend them forever to the admiration of out-laws! They opened the polls; they provided ways and means for their own party to vote; they bluffed and bullied all those who could not show the sign; they in fact converted the election into a perfect farce, without one redeeming or qualifying phase.

Peter Smith of The Courier-Journal wrote Moving through the main streets of town, the Protestant mobs attacked and slaughtered immigrant Catholics — with ropes, guns, clubs and pitchforks. At the end of what the Catholic bishop described as a daylong “reign of terror,” and what history would call Bloody Monday, at least 22 people were dead. By early morning, the polls were taken over by the American party who hindered the vote of every man who could not identify himself as a supporter of the American Party. In the Sixth Ward bullies drove two from the polls and forced them to run a gauntlet in which they were beat unmercifully, stoned and stabbed. In the afternoon a general row occurred on Shelby Street, extending from Main to Broadway where some 14 or 15 men were shot, two or three were killed, and a number of houses were broken into and pillaged. About 4 PM a crowd armed with shot-guns, muskets and rifles were about to attack the Catholic church on Shelby street when Louisville’s Mayor stopped them. An hour later the large brewery on Jefferson street, near the junction of Green, was set ablaze. Later, three Irishmen going down Main Street, near Eleventh, were attacked. The Irish fought back, firing from the windows of their houses on Main Street. After dusk, a row of frame houses on Main Street between Tenth and Eleventh, the property of Mr. Quinn, an Irishman, were torched. The flames spread across the street destroying 12 houses tenanted by Irish, and when any of the tenants tried to escape the flames, they were shot down. At least five men were burned to death, having been so badly wounded that they could not escape from the burning buildings. One elderly longtime citizen’s murdered body was thrown into the flames of his burning property. The victim’s only crime, lamented the Daily Democrat newspaper, was: that he was an Irishman and a Catholic. After all the outrages committed by the American Party that day, the mob having satisfied its appetite for blood, demonstrated against the Journal’s competitor newspapers – the Times and the Democrat offices, breaking a few windows, and burning the sign of the Times office.

The Rev. Clyde Crews, author of a history of the Archdiocese of Louisville, said that then-Louisville Bishop Martin Spalding and Protestant leaders began establishing this more tolerant environment immediately after Bloody Monday, when they called for calm rather than revenge.

On the Courier-Journal’s 150th anniversary, editor Keith Runyan wrote: Prentice’s raw bigotry is part of the past that we have to live with, but I don’t think that’s our legacy; the newspaper of 1855 was about as far as you can get from The Courier-Journal of 2005, Editorially, we always have been concerned in modern times about minority rights, about assimilation, about fair treatment of immigrants.

Today, Louisville has three private agencies for refugees and has gained national attention for such interfaith endeavors as its annual Festival of Faiths and its network of neighborhood community ministries. Present-day immigrants find Louisville very welcoming and open to people from not only Germany and Ireland but everywhere. In contrast to times past, there is such a wonderful ecumenical environment, noted Rev. Bill Hammer, head of the Office of Ecumenical and Inter-religious Relations for the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Louisville.

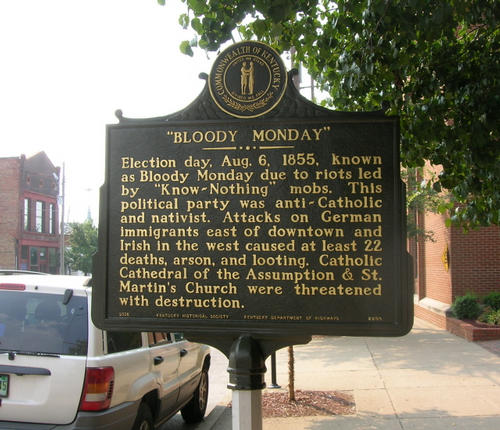

Then, in 1995, then AOH president Paul Whitty applied for a Bloody Monday historic marker to be placed between 10th and 11th Streets on West Main, the site of the burning of a row of frame houses owned by Patrick Quinn. In 2005, the 150th anniversary of the tragedy, metro government and civic groups sponsored a panel discussion and bus tour to places connected to the riots and the AOH and German-American Club raised funds to erect a marker which was unveiled on August 4, 2006 between 10th and 11th Streets on West Main Street. This month, America’s leading Irish Catholic organization – the Ancient Order of Hibernians – will be welcomed by the citizens of Louisville and especially the local Father Abram Ryan Division of that order, some of whose ancestors may have lived through that tragedy.