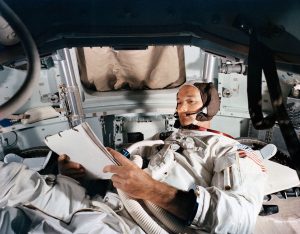

Major General Michael Collins, who as a Colonel was the Command Pilot of Apollo 11, the mission that put a man on the moon, is sadly often overlooked, but it should not be forgotten that the successful return of his crewmates Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin was dependent entirely on his piloting skill in flying the command module and performing a successful docking with the Lunar module.

Michael Collins was a second-generation Irish American born into a military family. Collin’s father was a career soldier, attaining the rank of Major General, earning two distinguished service medals and the Silver Star. The young Michael attended his father’s Alma Mater, the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, graduating in 1952. Graduates of West Point at that time were given the opportunity to transfer to the Air Force (there being no Air Force Academy at that time). The opportunities for exploration that aeronautics offered, combined with concerns that an Army career would always have a cloud of favoritism because of his father’s notoriety, influenced young Michael to choose the Air Force.

Collins became an expert pilot, one of an elite group of test pilots, and was eventually selected for astronaut training. Collins would first enter space as part of the two-man crew of Gemini 10. As part of the mission, Collins performed two spacewalks and docked several times with a target drone, which were vital preliminaries to the upcoming efforts to put a man on the moon. Collins described the experience during one spacewalk as “like a Roman god riding the skies in his chariot.” The less romantic NASA administration gave Collins an additional $24 in “travel money” for the three-day mission.

Collins is of course best remembered as a member of the three-man crew of Apollo 11, the first mission to put a man on the moon. It was Collins who designed the mission’s famous logo of an eagle landing on the moon with the Earth in the background. However, Collins’ expertise as a pilot meant that he was chosen to be the Command Module Pilot and would circle in orbit alone while Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the moon and would walk on its surface.

While the world watched amazed as Armstrong and Aldrin were on the Moon, Collins was alone in a tiny capsule, often out of radio contact with the Earth. “Not since Adam has any human known such solitude,” NASA public affairs officer Douglas Ward remarked, and we should not underestimate the fortitude and psychological strength that General Collins required to perform his mission successfully and return the first men to walk on the Moon to Earth. When later asked, “What were you thinking when your colleagues were out there making cosmic history?” Collins, with humor, replied, “I just kept reminding myself that every single component in this spacecraft was provided by the guy who submitted the cheapest tender.”

After the Apollo 11 mission, Michael Collins was appointed the Director of the National Air and Space Museum. Collins faced the monumental task of securing funding and overseeing the museum’s construction in time to open in time for the U.S. Bicentennial in 1976. The museum eventually received Congressional approval for a budget that necessitated some scale-backs due to financial constraints. Despite these challenges, including a tight deadline and the project’s ambitious scope, Collins’ leadership saw the museum opening ahead of schedule in July 1976. Collins managed the construction, staffing, and development of exhibits, making the museum one of the most visited in the world.

Michael Collins’ achievements, from his crucial role in the Apollo 11 mission to his work with the National Air and Space Museum, embody the contributions of Irish Americans to American history, aligning with the spirit of Irish American Heritage Month. His legacy underscores the significant impact of Irish Americans in pushing boundaries and advancing exploration. Collins’ life reflects the perseverance and innovative spirit celebrated during this month, highlighting the integral role of Irish American heritage in shaping America’s progress.

Neil F. Cosgrove ©