For many Irish Americans, watching John Ford’s ‘The Quiet Man” is as much a part of St. Patrick’s Day tradition as Frank Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life” is a part of Christmas. Both movies depict an idealized time and place that was much simpler than today, or in fact, ever was, but the basic themes of the importance of values and friendship still speak to us. Not to be overlooked in our enjoyment of “The Quiet Man” is the very complex man who gave us this movie, Irish American John Ford.

John Ford was born John Martin Feeney in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, on February 1, 1894. His parents were Gaelic-speaking immigrants; Ford’s father, a saloonkeeper and Democratic Party Ward boss, was born in Spiddal County Galway, his mother from the isle of Inishmore in the Aran Islands. Despite being one of eleven children, several of his siblings not surviving childhood, Ford grew up in reasonably comfortable surroundings. However, the slights and offenses he and his family endured as Irish Americans in Yankee-dominated New England forged a pugnacity that would mark his later life. In an era when all Americans were expected to assimilate, Ford took a defiant pride in his heritage and culture. As actor and fellow director Orson Wells would observe, “(Ford) had chips on his shoulder like epaulets.”

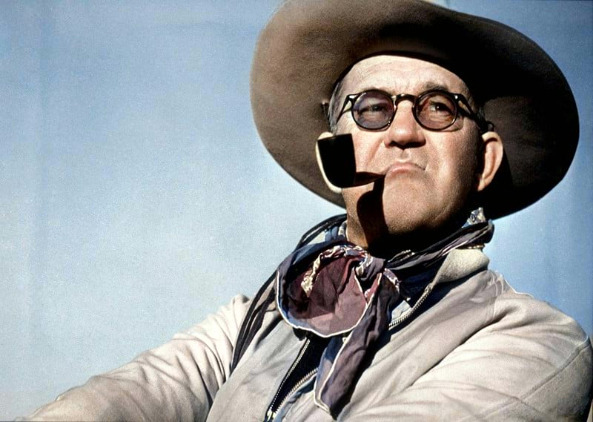

John Ford entered into a career in film after following his older brother Francis (who was the first to take the stage name of “Ford”), an already established actor and director of silent films, to California in 1914. He began a three-year apprenticeship where he learned his craft through being an assistant, handyman, stuntman, and occasionally an actor. In 1917 Ford was given his first film as a director, “The Tornado,” a movie in which he also starred. Per Ford, then Head of Universal Studios Carl Laemmle gave him the job of director with the recommendation, “Give Jack Ford the job—he yells good.” It is unlikely that Mr. Laemmle realized at the time that this 23-year-old young man who “yells good” would go on to make over 140 films and win six Academy Awards. Ford’s first film would also set the themes for the movies John Ford is most associated with: the West and the Irish. The film was a western where Ford himself played a cowboy who earns a $5,000 reward, which he sends to his mother in Ireland so she can keep the family home.

Ford pioneered location shooting and the “long shot,” where his characters are framed against a vast natural terrain such as Monument Valley, Utah, an area still called “John Ford Country.” Fellow directors Akira Kurosawa, Orson Welles, and Ingmar Bergman cited him as one of the greatest directors of all time. Orson Wells stated that he watched John Ford’s “Stagecoach” forty times before he began shooting “Citizen Kane“.

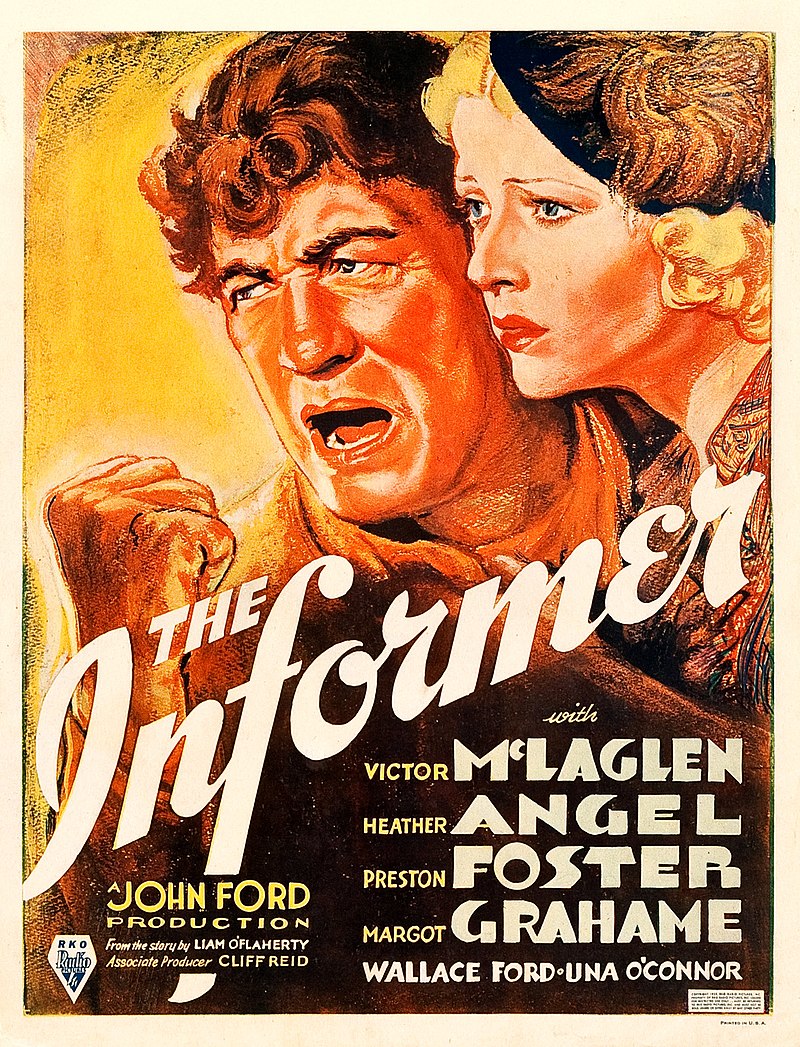

However, perhaps an even greater trademark of Ford is the inclusion of Irish American values in his films: Duty, Loyalty, Family, and the commitment to the values of one’s heritage within a bigger and sometimes hostile society. These are themes that are to be seen whether the subject matter was a coal mining town in Wales in “How Green was my Valley,” an isolated western cavalry post in “Fort Apache,” the struggles of an old-time party machine politician whose world is changing in “The Last Hurrah” or Ireland during the Black and Tan wars in “The Informer.” Many of Ford’s films are filled with Irish immigrants who are willing to sacrifice themselves so that future generations may advance up the social ladder, but never at the sacrifice of their cultural identity. Even in his Academy Award-winning film “The Grapes of Wrath” concerning Oklahoma farmers forced to leave their farms during the Great Depression, Ford saw parallels to Ireland’s Great Hunger.

Ford lived the values of loyalty and family off the screen. Ford and his actors bonded in an extended family (sometimes called The John Ford Stock Company) that he used, again and again, in his pictures; more than a few actors whom other directors rejected, thinking their marquee value had faded, could always find work with John Ford.

Another theme Ford embraced in film, and his personal life was that there was no conflict between being proud of one’s heritage and patriotism to one’s county. At the outbreak of WW II, John Ford joined the United State Navy, where his talents as a director were used to make morale-boosting documentaries, two of which earned Academy Awards. Ford was on Midway Island when the Japanese launched their attack and continued filming while in an exposed position, being wounded by enemy machine gun fire in the process. Ford was present on Omaha Beach on D-Day, landing himself with a team of Coast Guard Cameramen filming the landing while under heavy fire. In addition to being cited for bravery, John Ford eventually attained the rank of Rear Admiral.

While many great directors cite John Ford as their influence and consider him one of the great directors of all time, some unfairly applying today’s standards to works produced more than half a century ago, regarding his work as “Politically Incorrect” rather than realizing how revolutionary they were in the context of their own time. The film “Fort Apache” was unique for its time in portraying Native Americans sympathetically as victims of the U.S. government, a theme Ford revisited in his film “Cheyenne Autumn.” His film “Sgt. Rutledge” was perhaps the first major Holywood film to recognize the contribution of African American Buffalo Soldiers and the struggles they faced.

Others criticized works such as Ford’s “The Quiet Man” as overly simplistic or depicting an Ireland that never was and missing the point this is not a history of Ireland but a poetic story of a child of immigrants longing for a connection to his heritage. Ford tells us this clearly when the character Sean Thornton says, “Since I was a kid livin’ in a shack near the slag heaps, my mother’s told me about Innisfree …. Inishfree became another word for heaven to me.” Or perhaps the best response is one Ford gave to a film historian who was questioning why Ford deviated from history in his film “My Darling Clementine.” “Did you like the film?” Ford asked. The historian admitted it was one of his favorites. Ford replied sharply, “What more do you want?”

For those who still don’t understand, perhaps all that is left are John Ford’s words to Eugene O’Neill “If there is any single thing that explains either of us, it’s that we are Irish.”