A number of Irishmen were key to Washington’s success in crossing the Delaware River to take Trenton. Among them were two immigrants: Paddy Colvin and Sam McConkey, who ran two river ferries. In 1885, Rev A. Lambing wrote: when reading one of the Trenton papers, I saw the simple statement that the American forces under General Washington crossed the Delaware at Patrick Colvin’s ferry into Pennsylvania. Struck by his name, which at once denoted his nationality, I resolved to know more about him. He did, and he found that Patrick Colvin of Co. Cavan, Ireland bought a ferry and land on the river in 1772 when Morrisville, PA was known as Colvin’s Ferry. Considering the urgency when Washington’s forces needed to cross the Delaware, it was fortunate that two ferries were in the hands of patriots like Paddy Colvin and Sam McConkey who had no happy memories of the British in their homeland. Since no bridges spanned the river which had to be crossed quickly or be trapped on its banks, the ferries were of key importance. There were only four ferries in the area: Colvin’s Ferry, less than 2 miles from Trenton; McConkey’s Ferry, 9 miles above Trenton; Howell’s ferry, 4 miles above and Dunk’s ferry, 10 miles below. Colvin also knew who owned boats and where they could be found and gave all this information, as well as his ferry, to Washington’s service.

A number of Irishmen were key to Washington’s success in crossing the Delaware River to take Trenton. Among them were two immigrants: Paddy Colvin and Sam McConkey, who ran two river ferries. In 1885, Rev A. Lambing wrote: when reading one of the Trenton papers, I saw the simple statement that the American forces under General Washington crossed the Delaware at Patrick Colvin’s ferry into Pennsylvania. Struck by his name, which at once denoted his nationality, I resolved to know more about him. He did, and he found that Patrick Colvin of Co. Cavan, Ireland bought a ferry and land on the river in 1772 when Morrisville, PA was known as Colvin’s Ferry. Considering the urgency when Washington’s forces needed to cross the Delaware, it was fortunate that two ferries were in the hands of patriots like Paddy Colvin and Sam McConkey who had no happy memories of the British in their homeland. Since no bridges spanned the river which had to be crossed quickly or be trapped on its banks, the ferries were of key importance. There were only four ferries in the area: Colvin’s Ferry, less than 2 miles from Trenton; McConkey’s Ferry, 9 miles above Trenton; Howell’s ferry, 4 miles above and Dunk’s ferry, 10 miles below. Colvin also knew who owned boats and where they could be found and gave all this information, as well as his ferry, to Washington’s service.

At the end of 1776, Washington, retreating from New York, headed for the Delaware River with the British in hot pursuit. He sent a message to Congress to line up a fleet of boats at Trenton to get him across the Delaware into Pennsylvania. Irish-born Captain John Barry contacted his friend Paddy Colvin who set to the task. On December 3, Washington reached Trenton and his army was ferried across. Colvin was at his post until the army was safely across by December 8, when the British entered Trenton. An angry Cornwallis found all the boats moored on the Pennsylvania side of the river, which was now an impassable barrier between him and the disorganized patriot army he hoped to capture on the Jersey shore. Cornwallis left a force of Hessian mercenaries to hold Trenton and moved on to take Princeton.

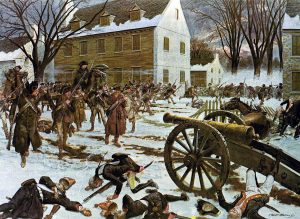

Meanwhile, in Pennsylvania, Washington set up camp about half a mile north of Colvin’s ferry. Concerned that the Brits would get their own boats to cross the river, Washington decided to re-cross on December 25 and surprise them first. Co. Armagh-born John Honeyman, a traveling butcher and former British soldier, had brought Washington details of the Hessian camp and informed the gullible Hessian commander that the colonials were in no shape to attack, suffering from cold, hunger and many were unshod. Washington arranged with Colvin to cross at several ferries and on the night of December 26, 1776, Washington quietly crossed back into New Jersey and captured Trenton from the unprepared Hessians. The Records of the American Catholic Historical Society (1889) reads: It was on that night that Washington crossed at McConkey’s or Colvin’s ferry. Colvin is a new hero whose services on that eventful night have been made known by recent historical investigation and recorded by John McCormack, the Catholic Historian of Trenton.

Meanwhile, in Pennsylvania, Washington set up camp about half a mile north of Colvin’s ferry. Concerned that the Brits would get their own boats to cross the river, Washington decided to re-cross on December 25 and surprise them first. Co. Armagh-born John Honeyman, a traveling butcher and former British soldier, had brought Washington details of the Hessian camp and informed the gullible Hessian commander that the colonials were in no shape to attack, suffering from cold, hunger and many were unshod. Washington arranged with Colvin to cross at several ferries and on the night of December 26, 1776, Washington quietly crossed back into New Jersey and captured Trenton from the unprepared Hessians. The Records of the American Catholic Historical Society (1889) reads: It was on that night that Washington crossed at McConkey’s or Colvin’s ferry. Colvin is a new hero whose services on that eventful night have been made known by recent historical investigation and recorded by John McCormack, the Catholic Historian of Trenton.

Washington knew that Cornwallis would soon be on his way to recapture Trenton and decided to stand and fight, but the rest of his army was still on the Pennsylvania side of the river. Davis’ History of Morrisville notes: A long fatiguing march to McConkey’s Ferry would have been a great hardship to men so severely tried. There seems to be no escaping the conclusion that they crossed at Colvin’s Ferry. Washington re-crossed the river and mustered the rest of his forces to cross and fortify Trenton before Cornwallis could arrive. On Dec 30, Washington brought his troops across on several Ferries. Meanwhile, Cornwallis, left two regiments at Princeton and marched back to take Trenton. Washington sent out small units, under Co. Offaly-born Col. Edward Hand, to harass the oncoming British. These units slowed Cornwallis down, but he still arrived late on January 2. Washington was ready, and the Second Battle of Trenton began.

Cornwallis’ attempted assaults failed due to cannon and rifle fire from Washington. Darkness fell, and Cornwallis withdrew for the night telling his army, Rest now, we’ll bag the fox in the morning. That night, Washington’s army built up their campfires to burn all night and silently slipped away. A force was left behind to noisily build fortifications and to cover the sound of the departing army. Washington’s force led by Gen. John Sullivan, son of Irish immigrants, snuck away in the night guided by another local Irishman, Paddy Lamb, along back roads around the British forces to launch a surprise attack on the small British force left in Princeton. Cornwallis awoke in the morning to distant cannon fire as the attack on Princeton had begun. Cornwallis divided his army and sent a force to relieve Princeton, but they were too late to prevent another American victory. Meanwhile, at Trenton the patriots defeated the reduced force left by Cornwallis. The British were driven back everywhere. As Washington went into winter quarters, he was master of New Jersey. The war had finally turned in his favor and new recruits poured in thanks to a patriotic group of Irishmen like Paddy Colvin, Sam McConkey, John Honeyman, Paddy Lamb, Col. Edward Hand, Gen. John Sullivan and the Irish recruits in the patriot army.

Colvin was a Catholic and McConkey was a Presbyterian. Yet these two Irishmen, laid their theological differences upon the altar of their country, and made common cause to secure our independence. It is a rule that has but few exceptions.

On April 6, 1789, after the revolution was won, Washington was declared the first President of the United States. Heading for New York and his inauguration, the Presidential Party left Philadelphia on April 21st in closed carriages. Again, Washington crossed the Delaware; this time he chose Colvin’s Ferry. At 10 AM, they arrived, and Irishman Bernie Hanlon fired a canon salute as dignitaries cheered. Paddy Colvin was given charge of the Presidential party and personally ferried them across the river, exchanging a familiar handshake and conversation with General Washington. According to William Stryker, Adjutant-General of New Jersey, Colvin was a committee of one to welcome the ‘Father of his Country’ on the banks of the historic Delaware. It gives him a prominence in history that he richly deserves, and which many may well envy. They had met there before under far different circumstances, when he had performed similar duties for the great Virginian. The banks of the river on the Jersey side were lined with Revolutionary officers and soldiers, and distinguished civilians of city and State; yet, in recognition of Patrick Colvin’s services and devotion to the principles of the Declaration of Independence, they paid him the compliment of permitting him to “take charge of the Presidential party.” In time of war he was the genius that made the icy Delaware subservient to his will. Now that peace had dawned, all felt he should be specially honored in his chosen sphere of operations, where he had no successful rival.

Historian John D. McCormack later wrote: Colvin was a Catholic and McConkey was a Presbyterian. Yet these two Irishmen, laid their theological differences upon the altar of their country, and made common cause to secure our independence. It is a rule that has but few exceptions. It is also a story that has few more laudable heroes than these Irishmen who helped to shape America.

Mike McCormack, National Historian

THIS IRISH AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH PROFILE IS PRESENTED BY THE ANCIENT ORDER OF HIBERNIANS (AOH.COM)

#IrishAmericanHeritageMonth #EmbraceYourIrishHeritageAOH